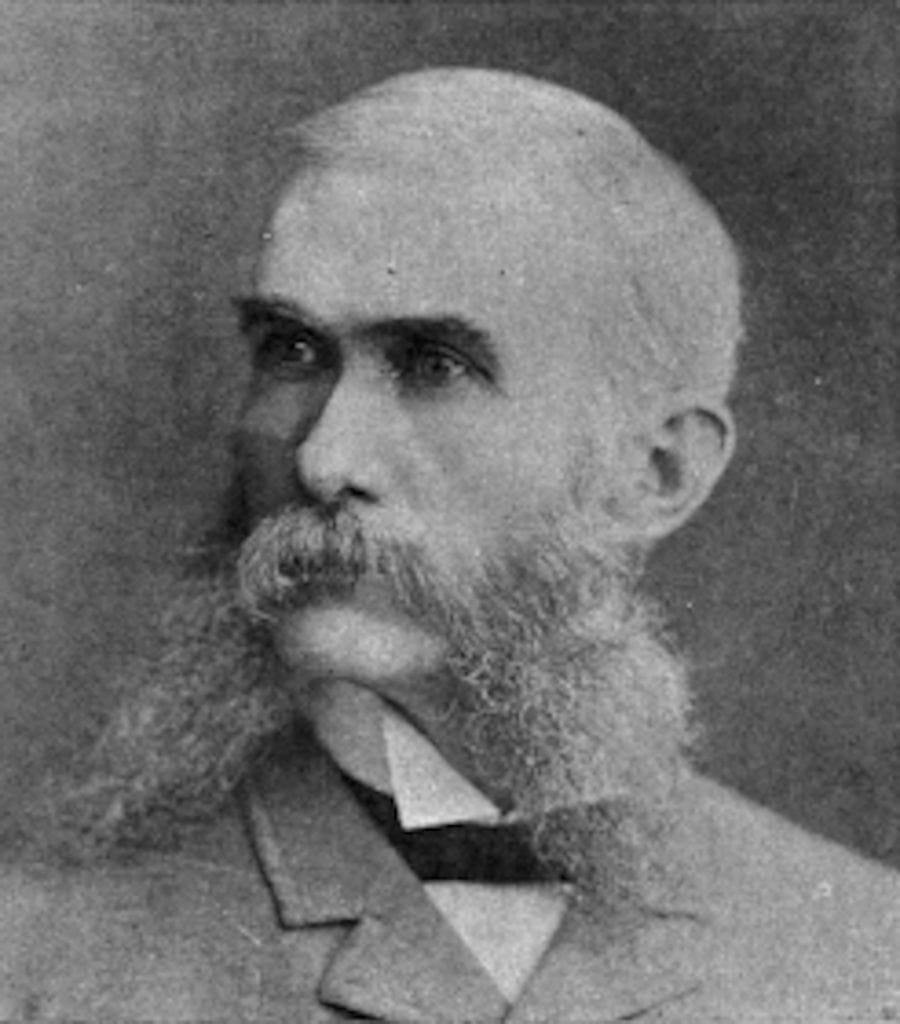

The famous American philosopher, Ralph Waldo Emerson, once said, “Sow a thought and you reap an action; sow an act and you reap a habit; sow a habit and you reap a character; sow a character and you reap a destiny.” For another man of Emerson’s time, James Addison Reavis, who would become Arizona’s most prolific swindler, this wisdom would have been an invaluable teacher. Reavis would have to learn the hard way.

It was May, of 1843, when Fenton and Maria Reavis welcomed a baby boy, whom they named, “James Addison Reavis,” into the world. The illusions of grandeur that would one day lead him down a path of corruption and moral decay, all began here, at home, in his formative years. Maria, the boy’s mother, believed herself to be descended from royalty; and her elevated self-worth left an indelible mark on the young Reavis, who now believed he too carried royal blood. This was the original thought.

Reavis was still a teenager when civil war broke out in the States. Missouri, where he was from, was split on union and confederate issues. Much of his views were informed by his mother, who believed the northerners would prevent her re-ascension to royal status. In her mind, a southern victory was assured and would propel her once again to the pinnacles of the social hierarchy. Convinced of this, she persuaded her son to enlist in the Confederate army. It was here, in the confederacy, thought became action, and action became habit.

His time among their ranks was short-lived but impactful; for it was here his con-game began. With exquisite attention to detail, he forged a myriad of military documents; the worst of which, perhaps, was the requisition of supplies, which he sold to locals. His forgeries were so consistent with that of his superiors, that it went unnoticed for his entire confederate career. Standing for nothing, good or bad, except what could serve himself, he played both sides; joining the union army after an apparent southern decline. Here his forgeries would continue for a short time, until he was discovered, and fled the country.

Later, he moved back to Missouri where he briefly conducted honest work as a streetcar operator, until moving into real estate. Remembering his successful forgeries from the service, he brought the same lessons to this new occupation. He fabricated his first land claim and used the fraudulent deed to sell it at an enormous profit. His actions had become habitual and produced in him a character of unrivaled arrogance.

He was in his latter twenties when he met Doctor George Willing, a fellow huckster. Willing possessed a number of land grants, having exchanged money and supplies, with a poor Mexican man known as Miguel Peralta, near the town of Prescott, Arizona; or so he said. Legitimate land grants were being honored by the U.S. government under the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, provided they were issued prior to 1848, with the annexing of the Southwest. Not fully convinced, but still interested, Reavis saw the opportunity for incredible wealth. Over a couple of years, the pair would devise different schemes to capitalize on these documents, now referred to as the “Peralta Papers.” After financial upheaval brought his real estate operations to a halt, in 1873, he shifted the majority of his efforts to the Peralta documents. It came about after a short time, in the course of their scheming, Willing turned up dead. Undaunted, Reavis saw opportunity. He swindled the bereaved family of Dr. Willing, loosening their possession of the deeds until he had what he wanted. Now with the papers in hand, it was a matter of patience and opportunity.

Opportunity would come, however, in the form of a railroad tycoon known as Collis P. Huntington. Reavis met Huntington while working as a reporter out of San Francisco. Perhaps a bit suspicious, but hungry for expansion, and wanting to prevent a similar agreement with another rail line, he was all-too-willing to grant Reavis a $2,000 advance to, as Reavis put it, “study the deeds”; with Reavis promising right-of-way privileges through the Arizona territory, and Huntington agreeing to pay royalties if things went according to plan. With that, he was sent back to Arizona. The year was 1880.

He began intensive studies pouring over Spanish land grants, how they worked, their handling in the territory, and how he might manipulate people to see things his way and bribe those who could not be persuaded. His research led him to the Mexico City archives where he spent weeks looking over official documents: land grants, birth reports, death reports, royal proclamations, and old maps; carefully observing every detail that brought a sense of authenticity. He even stole documents that he scrupulously duplicated, then returned to avoid suspicion.

With adequate research under his belt, the Peralta family was born; not of flesh and blood, but of the imagination of James Reavis (Peralta is a common Spanish name, similar to Smith in English. There was a Peralta family in Arizona history, but that’s a topic for another day). Reavis was certainly creative and went to great lengths in creating a plausible backstory for his work of fiction.

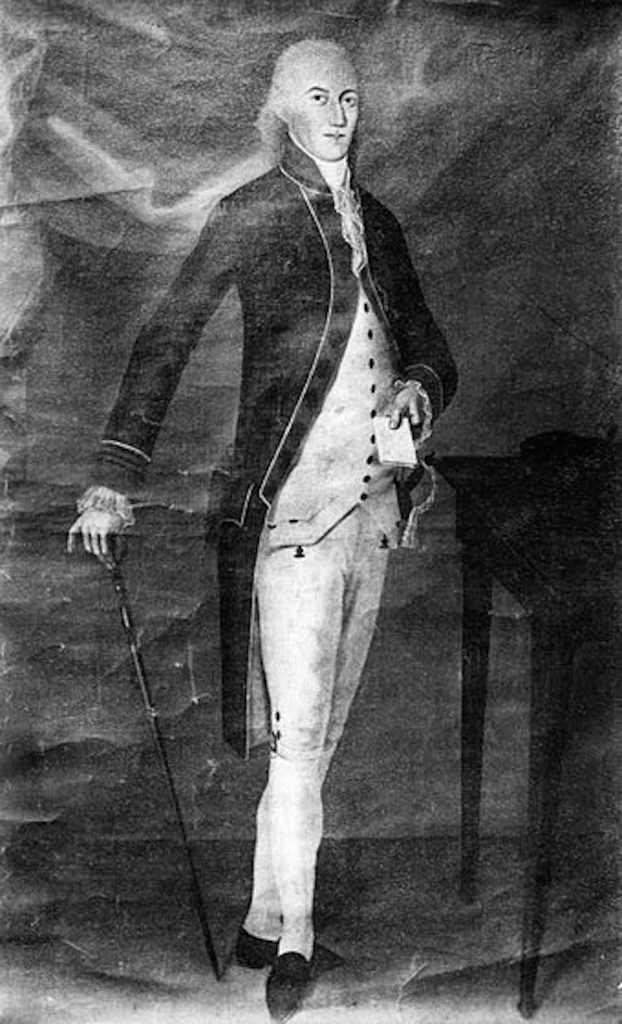

The Peraltas, according to Reavis, were of Spanish nobility, having garnered tremendous wealth in the seventeenth century. Don Miguel Nemecio Silva de Peralta y de Las Cordoba, born in 1708, the linchpin of his fabrication, was favored by both the Spanish and French crowns. Peralta served in the military for a number of years until being sent to Mexico where he would tend to the King’s affairs. He would be promoted to Captain General and gifted a large piece of land for his outstanding service, and the title of “Baron of the Colorados.”

His spurious tale would track Peralta’s movements into Arizona (still Mexico, at the time), where he was given full title to the land in 1772, and established a small Garrison, known as Arizonac, near the Ancient Hohokam Ruins known as Casa Grande. Some time passed, and when he was 62 years old, he was married and started a family. At age 73, he drew his will, leaving everything to his family, “heirs to the Barony of Arizonac.” His son, Miguel, who would later marry a woman of nobility from Guadalajara, inherited his estate upon his death at the age of 116. Together, they produced a daughter, whom they named Sophia. Fearing the hostile climate of the Southwest during those days, with the Civil War and native uprisings, they chose to remain outside Arizonac. However, over the course of time, the Peralta empire crumbled, leaving an elderly Miguel poor and destitute; the same Miguel who sold the deeds to Dr. Willing.

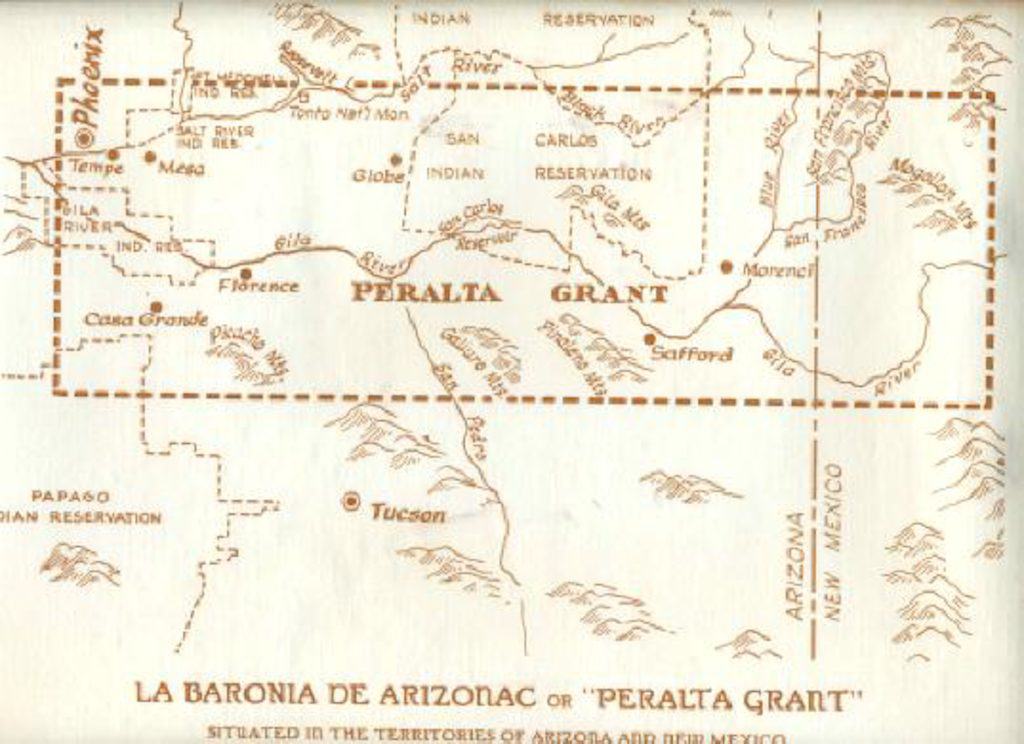

Armed with a story he felt was sufficiently convincing, and dozens of fake documents, he arrived in Tucson in September of 1882. His claims to the land were laughable to many of that time, but to others, they were of great concern; and soon many landowners, miners, wealthy businessmen, and settlers, were in a frenzy. Unable to coordinate with the surveyor general’s office at the time, he instead left for San Francisco, where he befriended George Hearst, a newspaper magnate. Hearst allowed him to promote the Peralta grant which, to many, validated his claims to the land. Returning once again to Tucson, this time in the company of a disbarred lawyer, they demanded the documents be examined. The more Joseph Robbins, the man in charge, examined the papers, the more concerned he became about their apparent authenticity. The area marked by the claim measured an absurd 75 miles by 250 miles, spanning from central Arizona, well into New Mexico; larger than New Jersey and Delaware combined! Robbins would have to file a report with the federal government before making an informed decision.

His successes up to this point had bolstered his vanity; he could do no wrong. Tapping into investor funds, and hiring Tohono O’odham laborers (Pagago), he built for himself a lavish mansion, in Arizola, Arizona; on the site of the Arizonac garrison, mentioned previously. Believing his lies would go undetected, he proceeded to strongarm the local population of ranchers, miners, farmers, and whoever else took up residence or operated on “his land”. Of his successful shakedowns, one of the most prominent came in the form of Colonel James Barney, president of the Silver King Mine, outside modern-day Superior. Barney, not wanting to compromise a successful $6,000,000 a year operation, folded easily, paying out $25,000 in blackmail funds. Emboldened by this victory, he carried on with brazen assurance. He hired lowlife thugs in the form of mercenaries and gunslingers to harass people into compliance; those who played ball were allowed to stay, and those who refused would suffer the consequences.

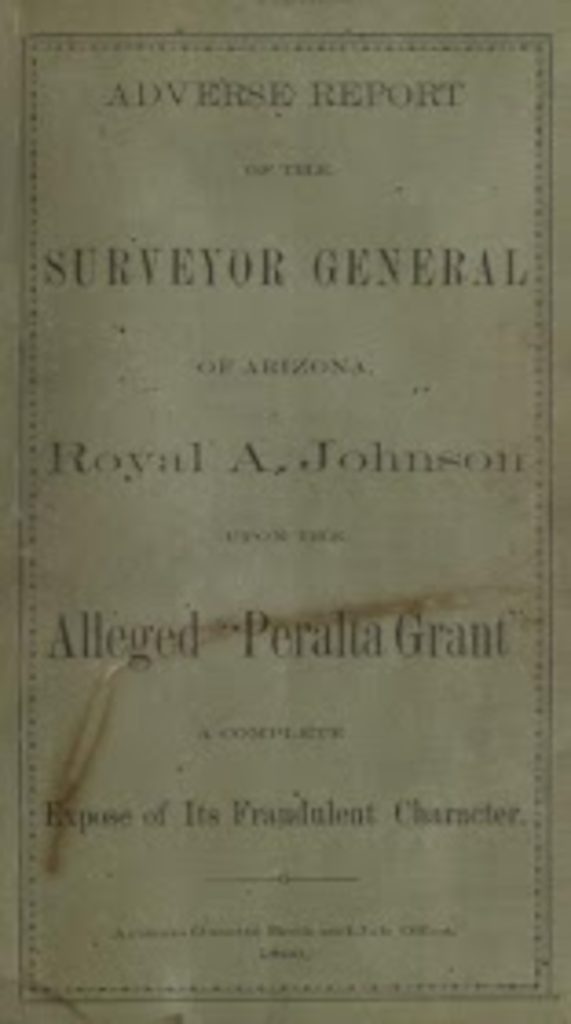

This would result in legal trouble, as a swarm of angry territorial newspapers made their rounds, leading to court hearings where he shared letters and documents signed by many willing tenants. The case was dropped after a year. According to rumors of the day, the federal government offered to pay millions of dollars to Reavis, if he would simply relinquish his rights to the land; this, however, was rescinded after a new administration took office in 1884. With this new administration came a new surveyor general, Royal Johnson. Johnson was no slouch and wasted little time branding the Peralta Papers as fraudulent. With trouble on the horizon, Reavis fled the territory.

This, however, was a minor setback. Reavis realized the only way to regain his lost fortune was to be legally bound to it. He needed an heiress to the Peralta fortune, and he knew how to find one.

While living in California, he met a young woman, to whom he retold all his fanciful stories. He told her she bore a striking resemblance to Sophia, the only known heir to the Peralta fortune. She hung on every word. An orphan, without a penny to her name, and having no one else in the world, she too was conned by Reavis. Perhaps on some level, she knew it was too good to be true, but she was still quite young, impressionable, and with little-to-no knowledge of her lineage. Reavis must have seemed like an angel from Heaven.

He gave her a new name with a new title: doña Carmelita Sofia Micaela de Peralta, Baroness of Arizona. He sent her to a convent where she would be provided education, and learn the social etiquette necessary to maintain a facade of royalty.

While she was away, he went to San Bernardino, where he tricked a priest into granting him access to birth records, where he swapped names to validate Sofia’s heritage. Unbeknownst to Reavis, and contributing to his eventual undoing, the church kept a second set of birth records.

It was around this time he made his return to Arizona. With renewed confidence, he sought to further attest his claim to the land. Amongst scores of authentic Hohokam petroglyphs outside the Phoenix Metro, he crudely scratched enigmatic symbols onto the rock face, which he later claimed referred to the Peralta family and Spanish royalty, even photographing his soon-to-be wife next to the supposed marker. This “Inicial Monument,” as they called it, marked the Westernmost boundary of his counterfeit land claim.

Once Sofia had finished her education and returned to him, the two were wedded, and he gave himself the title, “Baron of Arizona.”

They briefly returned to San Francisco where they collected financial backing to form a company, which he then sold shares to, knowing they were utterly worthless—another scam. Then, traveling to New York, he rekindled a relationship with Senator Conkling, whose influence he used to great effect.

From his wealth and marriage, he enjoyed extraordinary privilege; so much so, when they later left for Spain, their arrival was treated like that of royalty. They enjoyed lofty access to the courts and to normally-restricted national archives, where he again forged documents. He went to great lengths to sell his story, even buying paintings of long-deceased individuals to pass off as members of the Peralta line, to share with his new Spanish affiliations.

Their international tour continued onto England, where they were welcomed by Queen Victoria, herself. Representing themselves as the Baronies of Arizona, they attended celebrations reserved for the world’s legitimate monarchs.

After returning home to deal with a brief legal stint involving the father of the deceased Dr. Willing, he formed the Casa Grande Corporation, which he informed investors was worth $500,000,000, making him inordinate amounts of cash. He safeguarded his ignoble empire with a well-known lawyer and the protection of Senator Conkling.

Royal Johnson, the man who had incriminated him years earlier, resumed his position as surveyor general. He had compiled a mountain of evidence against Reavis in a lengthy report that he sent to Washington, detailing every little discrepancy he could find in the Peralta documents. He noted poor spelling and grammar sprinkled capriciously throughout, inconsistent with royal clerks; a number of other alterations were also discovered, including wrong-century typefaces, and more. The evidence could not be reasonably overturned.

Reavis, arrogant as he was, responded as you might expect; he sued the U.S. government for the towering sum of $11,000,000, arguing their slanderous allegations had caused him developmental fallout and a lot of money. Facing little ramifications over the years, he proudly believed himself unstoppable; and so he thought little of bringing his suit to the Court of Private Land Claims, in Santa Fe, where he surely expected another victory. The government hired Matthew Reynolds, a gifted attorney, to take the case. Reynolds was up to the challenge and began a thorough investigation in preparation for a hearing.

Reavis prepared the only way he knew how, through fraud, hiring witnesses to perjure themselves, and enticing groups of supporters to defend him in court. However, agents at this time had uncovered his handy work both in Spain and San Bernardino. His shady witnesses buckled under the weight of evidence, and his friends and supporters abandoned the sinking ship.

When his day in court came, at last, he had no choice but to defend himself, as he had no money left for an attorney. His pride kept him from an appearance at his own hearing for three days, during which time, an unbreakable case was levied against him. He tried to have the case dismissed; when that didn’t work, he showered the jury with grandiloquent words, only adding to his pompous veneer. All his efforts fell flat, and in June of 1895, the court ruled the Peralta papers a sham.

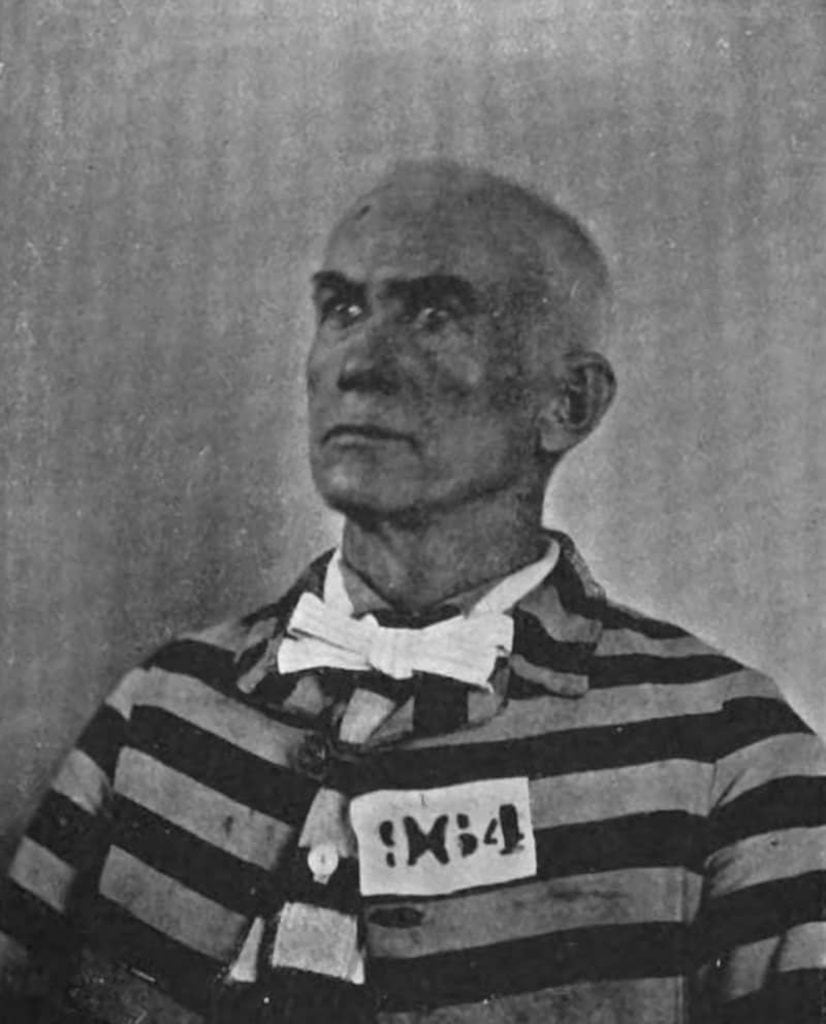

He had barely left the courthouse when he was arrested by a federal marshal for attempted fraud. After some time in jail, and his civil trial, he was given an undoubtedly lenient sentence of only two years in federal prison and a $5,000 unpayable fine.

Despite his continued scheming, no one would ever take him seriously again, and the remainder of his life was spent in poverty. In 1902, his wife, Sofia, divorced him, moving herself and their children to Colorado, where she would profit selling her version of events to various publications; while he found himself in a Los Angeles poor house, where he would eventually die, in 1914; and later buried in Colorado. He spent a dozen years cheating others out of their hard-earned fortunes (1883 to 1895). Reavis had sowed a character, and reaped a destiny; dying penniless, alone, and hated by all who knew him.

“Pride goeth before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall.” – Proverbs 16:18

A movie entitled, “The Baron of Arizona,” based on his life events, debuted in 1950; and a book was published of the same name (you can find the movie for free on YouTube).

Today, a historical marker is all that remains of his former property, in Arizola, Arizona (other than some plumbing). You can visit this site for yourself on the Northeast corner of Jimmie Kerr Boulevard and Noble Street.

Contribute to Arizona Jones

Hey everyone, thanks for reading! If you would like to help me continue to put out educational content like this, please support my work through one of the following:

GiveSendGo

Patreon

Official Arizona Jones Store

Sources

Sam Lowe. “Arizona Myths and Legends.”

Donald M. Powell. “A Lost Arizona Story.”

Marshall Trimb. “The Lost Dutchman Mine: Fact or Fiction.”

Jeff Jackson. “Reavis put Arizola on map ignominiously.”