It was 2:30 in the morning on Independence Day, when two of my friends, Kaleb (AKA, Squatch) and Ryan, arrived at my door. We had a planned adventure that day based on a tip I had received. With three hours until sunrise, we hit the road. Our destination: a rock quarry hiding something more than its namesake.

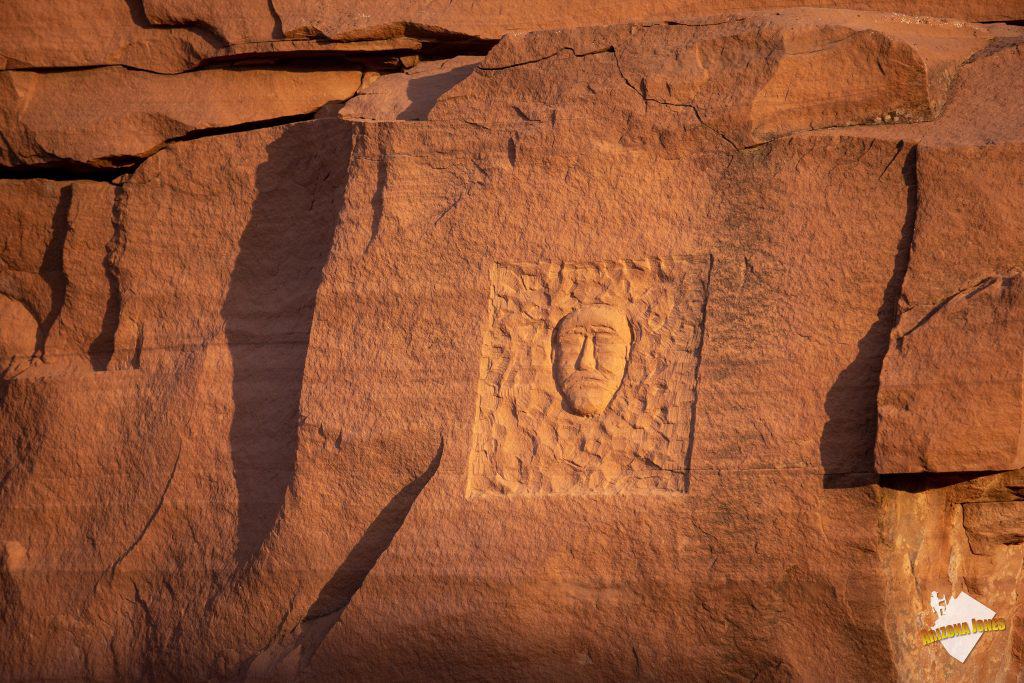

We arrived in the fading twilight. Heading toward the nearest wall, we passed a heap of large, worked stones with obvious tool markings. We continued north along the wall, with the anticipation that each turned corner might produce the very thing we were looking for. The piles of unwanted earth continued, even as we reached an unused portion of the quarry. Suddenly, I hear Kaleb, with all the enthusiasm of watching paint dry, say, “found them”. There it was, a face had emerged from the sandstone!

Within minutes we found 3 faces; 2 embedded in the quarry walls, and one up a level and carved into a boulder; each distinguished in its own way; all remarkably detailed.

So, what’s their story? Unfortunately, answers are hard to come by; but we have some clues, beginning with the quarry, and the engravings, themselves. Let’s investigate.

We find our starting point with the first engraving, that of a man in profile, reminiscent of the Lincoln penny, including a timestamp of 1862. A nearby relief of a moustached man with a long beard bears an inscription with the name, H. Lantry. Finally, the last figure is of a bald and unhappy-looking man (think Jeff Dunham’s Walter); eyes closed, and rendered over a textured background. We have a time; we have a name — can we connect these to the quarry? What was happening in 1862?

As it happens, America was in the midst of transition, having acquired the Arizona Territory, only years before, and much of the nation still sick with gold fever, with the California Gold Rush scarcely behind them. Arizona, at this time was seen, in some ways, as more of an obstacle than a destination; but would experience a population boom with its own gold rush, starting in the late 1850s.

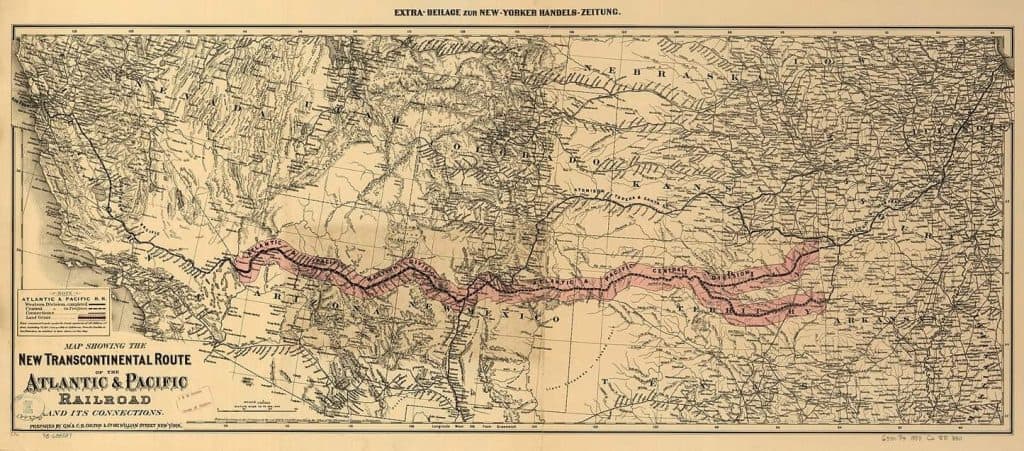

The dream of an interconnected America echoed through the Halls of Congress, and soon, a number of topographical surveys were commissioned across the West, employing the likes of Captain Lorenzo Sitegraves, Lieutenant Amiel Whipple, and Lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald Beale, cementing their legacies in the annals of Arizona history, as they scouted a route for the upcoming transcontinental railroad; followed in 1862 by legislation, in the Pacific Railroad Acts; incentivizing the cooperation of private corporations.

Railroad construction would not begin, however, for almost another two decades; post-dating the encryptions; thereby eliminating quarry workers as potential suspects. Even so, it would be used in the construction of railroad bridge abutments and column bases, as seen along the floor of Canyon Diablo; and is located directly south of the modern-day tracks.

𝗥𝗲𝗹𝗮𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝗔𝗿𝘁𝗶𝗰𝗹𝗲: The Story of Two Guns, Apache Death Cave, and Canyon Diablo

Still, the surveyors of prior years, and their expedition members, certainly passed through here. Could it be that a skilled sculptor or two were hidden among their ranks? This is unlikely, as these parties predate the 1862 imperative. A trail, known as the Beale Wagon Road, a beneficiary of the previously-mentioned surveys, was active at the time. While it’s not unreasonable to assume this road brought the artistic talent responsible for the engraved images, I have my doubts. One possiblity fits better than all the others…

H. Lantry, mentioned earlier, might just be Henry E. Lantry, son of Barney Bernard Lantry (B. Lantry), a known stone mason of the 19th century. Lantry was a bridge builder, and a construction contractor for the railroads; running a profitable construction company with his brother, Charles. Throughout his career, he acquired a number of stone quarries, and in fact, this same quarry might have been in his possession, though I can’t confirm. Lantry was not unfamiliar with stone cutting; he studied the trade, actually, in Vermont, for a number of years prior to his time in Arizona. Lantry had one more son, Charles John Lawler Lantry.

Of the 3 figures found onsite, it’s likely the profile figure is B. Lantry, himself; The bearded-figure, his son, Henry; and the third, his other son, Charles. In 1862, Henry would have been no older than 4 years old, and Charles had not yet been born. My interpretation of the evidence suggests the profile image of Lantry was the initial engraving in 1862, followed by the other two, probably created in the 1880s, by his sons who had become skilled craftsmen in their own right.

While this is not without speculation, it does seem to harmonize the date, the name, skills, location history, and even the total number of engravings. I think we have our answer!

Special thanks to Bob Sands and Emily Sisk for their contributions to this article.

𝗞𝗲𝗲𝗽 𝗠𝗲 𝗜𝗻 𝗕𝘂𝘀𝗶𝗻𝗲𝘀𝘀: Join theazjones.locals.com. The only way I can continue bringing these articles to you is with support.

Sources

azmemory.azlibrary.gov, “Atlantic & Pacific RR Co.”

findagrave.com, “Barney ‘Barnaby or Big Barney’ Lantry.”

genealogy.com, “Re: Barney Bernard Lantry of Wisconsin & Kansas.”

newspapers.com, “The Topeka Daily Capital”.