I’m sure many of you are familiar with Cibecue Creek, a tributary to the Salt River, in the White Mountains of Eastern Arizona, from which flows the beautiful Cibecue Falls. Did you know, however, these tranquil waters were host to a bloody massacre in the latter 1800s?

In the years leading to this night, following the forced exodus of many Apache and Yavapai peoples from their homelands, in what would be remembered as the March of Tears (not to be confused with the Trail of Tears)—a horrific event claiming the lives of many natives as they marched over mountains and crossed raging rivers, in the dead of winter, onto a reservation they had no interest in being (this is truly a dark stain on our State’s history—and on another day, I will write extensively on this event).

The year was 1875. The Apache and Yavapai were forced to live together on the San Carlos Reservation. The government drew no distinction between the two groups. There was no harmony between them, and problems arose predictably and often. It seemed their only common ground was their hatred for the white man, which although many white men and women opposed the injustices faced by the natives, was an understandable regard.

J.C. Tiffany was the assigned Indian Agent during this time—that is, a sort of liaison between the government and the native population. Tiffany was ridiculously corrupt, and caused many undue hardships for the San Carlos population. Among his many offenses, he cheated the natives; he stole their livestock; withheld and sold supplies that were meant for their benefit, and kept the money for himself; and he allowed his friends to plunder the reservation. It seemed his every act fomented unrest amongst the people he was meant to serve.

It was around this time, in the early 1880s, that a change in religious practice was adopted by the natives on the reservation. A ceremonial affair that became known as the ‘Ghost Dance,’ was incorporated into their religious observations. Nockay-del-klinne, a White Mountain Apache, and medicine man, although not the originator of this new ideology, created his own version of it. His orthodoxy preached the resurrection of their stolen lands, and of their dead, and envisioned the destruction and eviction of the white population, by the time the corn grew tall.

To many non-natives involved with the reservation, including soldiers and officials, this new religious practice was of great concern. This was because for the first time since entering the reservation, these opposing forces—Apache and Yavapai—were united in the dance, and fear of another uprising was at the forefront.

This same man, just a decade prior, was sent to Washington to speak with President Grant. When he returned, he was enlisted as an Apache Scout—Scouts were skilled trackers, and would help the U.S. Army track what they deemed ‘hostile indians.’ Although he was quite young at the time—only in his twenties—he commanded much respect amongst his native brethren, and was seen as a peaceful and influential man.

Agent Tiffany, before being relieved of his position, convinced Colonel Eugene A. Carr, commander of troops at Fort Apache, that this Ghost Dance religion must be broken, and Nockay-del-klinne arrested, or killed if he were to resist.

So Carr, leaving for Cibecue Creek, took with him a small army consisting of 23 White Mountain Indian Scouts, 10 civilians, and 121 troopers, to take into custody the young shaman.

According to the Army’s official report, after much pleading, Nockay-del-klinne agreed to come peacefully. This, however, is not the version reported by the natives. Their version accounts a forceful removal from his wikiup, by a Captain Hentig, dragging him out by his hair, to be put under watch in a tent. Enraged by this display, the native scouts plotted a mutiny.

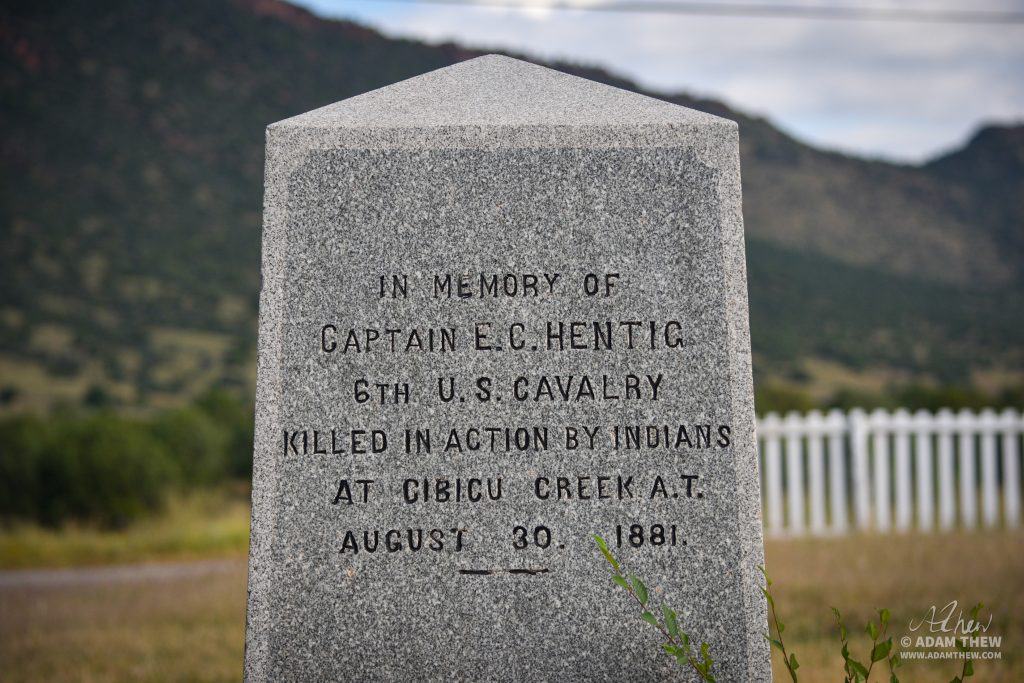

An Apache Scout, Sergeant Dead-Shot, requested the scout’s encampment be nearer to that of the natives because of some supposed ant hills in their allotted space. Once they had moved position, he let out a loud war cry, and he, and his fellow scouts barraged the soldier’s encampment with heavy fire. Captain Hentig, the one they had accused of humiliating their young shaman, was the first to die.

During the confusion, the soldier guarding Nockay-del-klinne, did as he was ordered by Col. Carr, and shot him in the head. According to the official story, this did not result in instant death; but as he crawled away, he was shot once more in the head; this time, fatally. Other witness reports allege he was instead decapitated with an ax.

When morning came, 8 troopers, and 18 natives (including the shaman, and 6 of the treacherous White Mountain Apache scouts), were dead. This would lead to even more raids against settlers and soldiers.

Eventually, these betrayers were rounded up and executed in March of 1882, by the noose—Dead-Shot, and two of his co-conspirators—at Fort Grant. Allegedly, Dead-Shot’s bereaved wife hung herself from a tree on the San Carlos reservation that same day. Before their demise, the scouts placed a curse on the attending priest and commanding officer, who both died of natural causes sometime later.

General George Crook would be summoned to the reservation to clean up the mess. Two months into his visit, he had cleaned out the squatters, miners, and other friends of agent Tiffany. He then, through the Office of Indian Affairs, relieved Tiffany of his position. Tiffany, through his avarice, had caused many untold hardships for these natives, and was largely responsible for the subsequent mutiny and massacre.

A memorial was erected on-site, and later was moved to Fort Apache Historical Park, to rest outside Gen. Crook’s cabin.

Sources

Kate Ruland-Thorne. The Yavapai: Sedona’s Native People. Pages 49, 72-74.

I hope you enjoyed that read! If you would like to support my work, please consider one of the following:

GiveSendGo: https://www.givesendgo.com/theazjones

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/theazjones

Store: https://www.theazjones.com/store