𝗝𝘂𝗹𝘆 𝟮𝟭, 𝟭𝟵𝟬𝟳

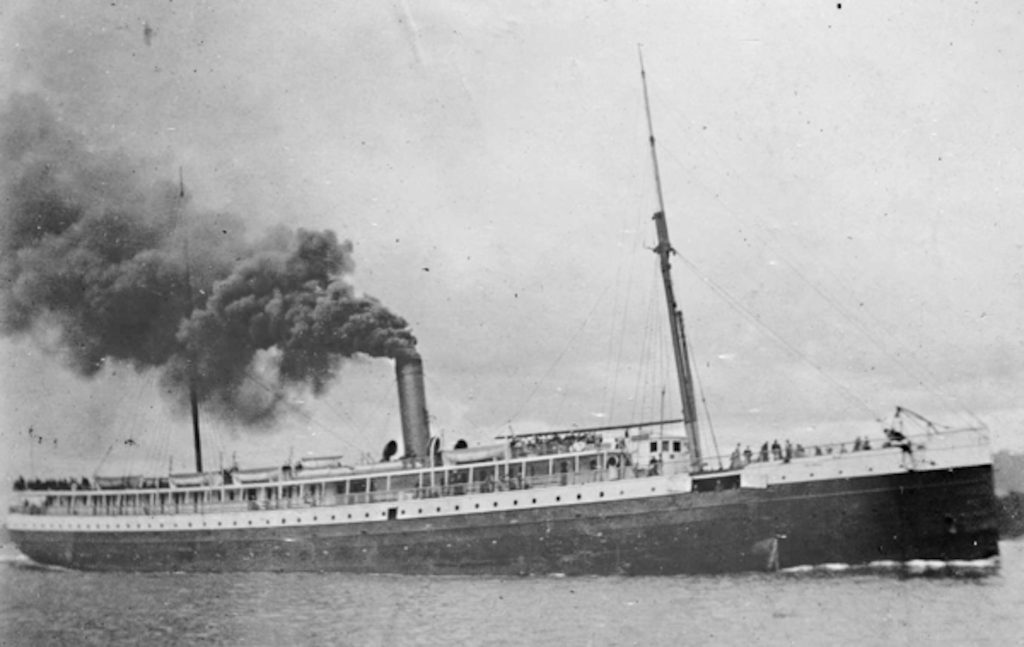

You’re aboard the steamship, Columbia, en route to Portland. San Francisco, wherefrom you departed the day before, now seems a distant memory. It’s dark, almost pitch black, and thick fog blankets the sea. An otherwise cold night is made bearable under the gleam of a state-of-the-art lighting apparatus, the first of its kind in seafaring vessels. Reaching into your vest, you remove a small pocket watch. It’s just past midnight, you observe, turning it slightly into the cabin’s incandescent glow.

Glancing out your porthole window, you imagine the shoreline, were you able to see it. The ocean waves become hypnotic almost, lulling you into a state of unconsciousness. CHOOOOO! You’re startled from your sleep…what was that noise? It’s nothing, you think, as you cushion your face against your pillow. Again you hear it, CHOOOOOOOO! This time louder and more abrasive — whatever it is, it’s getting closer.

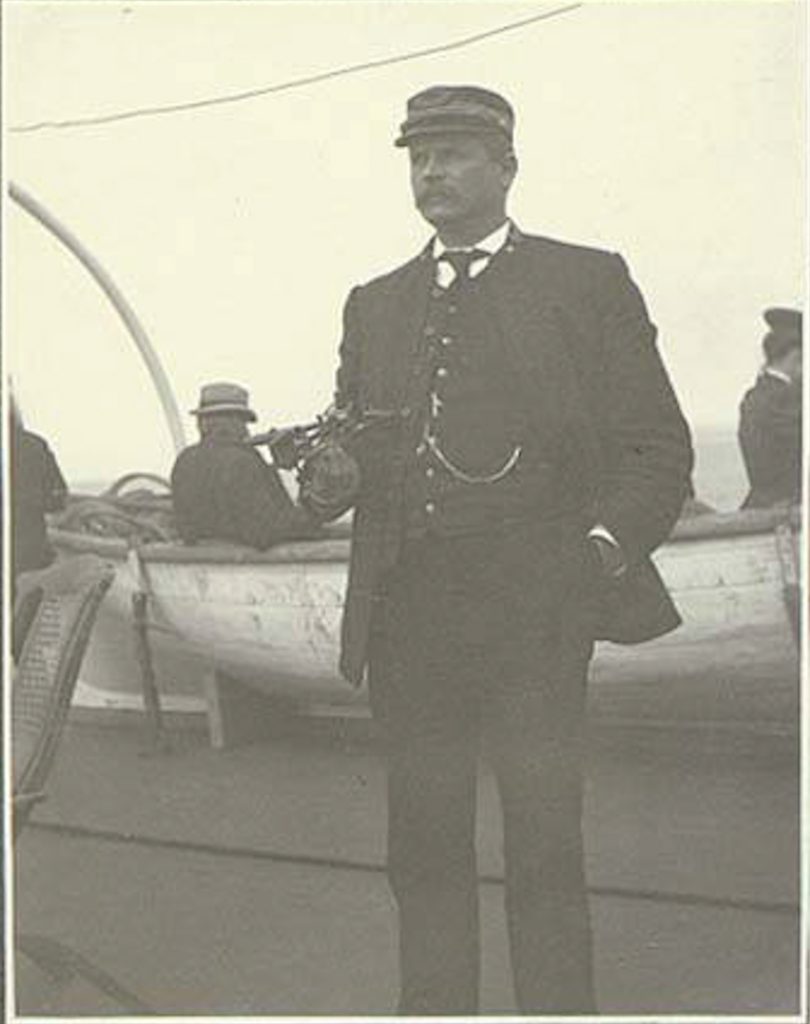

Alarmed, you make your way on deck, now absorbed in a thick cloud of ocean vapor. You scarcely sense the chill in the air, as adrenaline surges to every corner of your body. Churning waves collapsing on themselves and along the hull of the ship, break an otherwise deafening silence. Word comes from Captain Doran: “There’s nothing to worry about”, he said, trying to calm the angsty passengers. It worked. He had done this before, after all, and blaring fog horns were standard fare. With your mind at ease, you retreat below deck.

No sooner after having shut the door behind you, you hear it, CHOOOOOOOO! This time more pronounced than ever before. Again and again, it blares in quick succession. Clammy hands attempt to soothe the burgeoning lump in your throat. You feel it in your bones: dread. Peering out the window, now you see it, a silhouette through the fog — another vessel rapidly approaches! Commotion erupts from the wheelhouse; “Full reverse!” You arrived in time to hear the captain shout, but it was too late.

𝟭𝟮:𝟮𝟮 𝗮.𝗺.

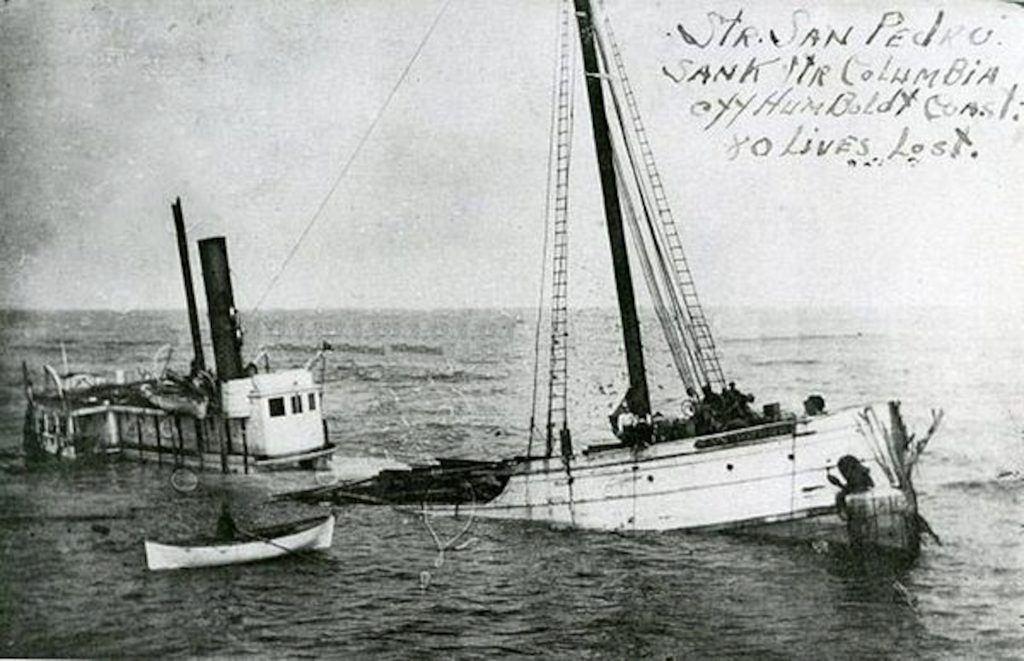

CLAAAANG! The whole ship quaked violently, broadsided by the San Pedro Steam Schooner, on the starboard side. The hull shrieked as it tore open. “What are you doing, man?!”, you hear the captain roar as the schooner pulls away. The Columbia begins to sink.

Terrified passengers flocked topside. Captain Doran, with a level head, ordered everyone to abandon ship. Unbeknownst to you, the [barely] still-floating San Pedro had released its own lifeboats in an attempt to help those now overboard. The ship, quickly taking on water, leaned starboard, throwing some people overboard. You watch as a small overloaded craft desperately attempts escape, only to be sucked under the ship as it falls to one side.

There, in the midst of chaos, you remember your wife and children. Just yesterday you were waving goodbye, promising to see them soon. Now…you just don’t know. You close your eyes and pray. Time is running out…

You wait until the last minute, just before the once-mighty vessel sinks beneath the waves, before jumping in and clinging to some floating debris. The captain, still at his post, goes down with the ship. You float there in the frigid waters, awaiting rescue, for what feels like a lifetime. Soon, other ships arrive to help the remaining survivors. You’re one of the lucky ones.

It took less than ten minutes from the time of impact for the Columbia to sink entirely beneath the waves. Eighty-eight lives were lost that night: men, women, children; entire families gone.

This occurred only a few miles west of Shelter Cove, about 200 miles north of San Francisco. This wasn’t the first wreck in the area, and in fact, at least 8 wrecks were recorded previously. It wasn’t until the sinking of the Columbia, however, that the United States Congress finally approved a $60,000 budget for the construction of a lighthouse at Punta Gorda, around 20 miles north of the wreck site.

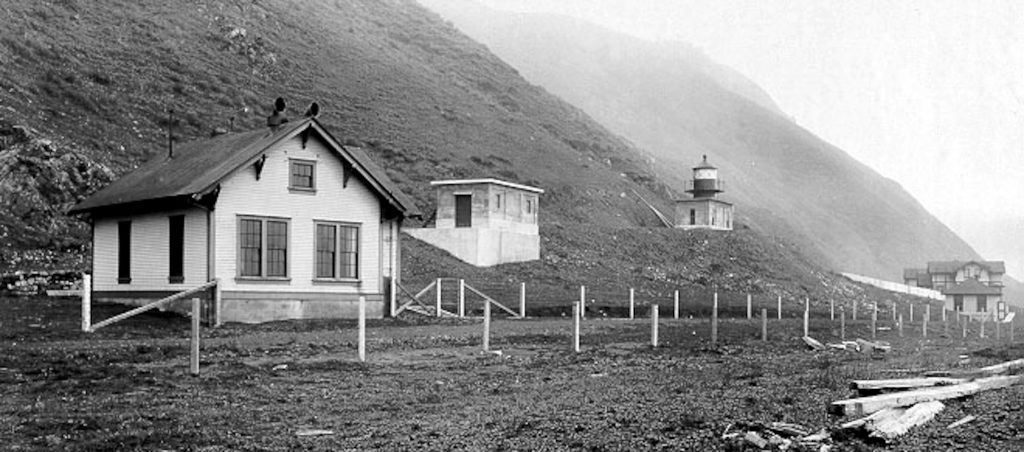

Construction began in 1910, and within a year, a small hamlet consisting of 3 houses with companion storage sheds, a barn, a fog signal, and a blacksmith shop, were all fully erected; followed in 1911 by its first gas-powered air siren, and later, the lighthouse; its first light shown on January 15, 1912.

The lighthouse still stands to this day.

𝟭𝟬𝟵 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿𝘀, 𝟲 𝗺𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗵𝘀, 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝟭𝟵 𝗱𝗮𝘆𝘀 𝗹𝗮𝘁𝗲𝗿 (𝗔𝘂𝗴𝘂𝘀𝘁 𝟯, 𝟮𝟬𝟮𝟭)

It was summertime, but the air was cool as we opened the car doors, and stepped onto the beach. My friend “Squatch” and I were in Northern California, about two hours south of Eureka, at a small campground wedged tightly between the Mattole River and the Pacific. It was getting dark and the whole beach was swallowed up by a dense sea fog, typical during summer months, not unlike that fateful night in 1907. We were separated from the water’s edge by about 150 yards or so, and a small sand embankment. We could hear the ocean, but not see it without first ascending the embankment.

Our journey up the coast wasn’t so dissimilar from that of the Columbia. Granted, we were not on the water and had no intentions of wrecking my car, but we did depart from San Francisco hours before, and ended the day’s journey only a couple dozen miles north of its watery tomb.

Tomorrow we’ll hike south along The Lost Coast Trail. Approximately 3 miles of coastline, interrupted only by a shallow creek, are all that stand between us and the lighthouse. Tonight, however, we’ll trade the whir of a ceiling fan, for the susurration of the tide, and the whispers on the breeze; we’re camping on the beach!

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗻𝗲𝘅𝘁 𝗱𝗮𝘆

We arose early the next day, not long after sunrise. After a quick breakfast, we hit the trail. We made it about a quarter mile before we decided we didn’t want to hike 3+ miles on loose sand. Looking at the map, we spotted an old dirt road coming down from the hills overlooking the beach. This road, I later discovered, was built in the 1930s, to make traffic to and from the lighthouse less cumbersome. It seemed fitting then, that we should use this road for the same purpose. It would shave off time and distance, and most importantly, mitigate our hiking through the sand. Now back at the car, we made our way to the top of the hill.

We found our road and parked there, at the top of the hill, and resumed the hike, following the road, as it meandered through the hillside. The fog slowly lifted as we made our descent, parting like a curtain, unveiling a freshly dewed countryside, lush with green and sporadic colonies of yellow poppies, rolling into a gorge beside us, and the creek at its base.

The wind picked up as we neared the beach. One could almost taste the salt in the air. I remember seeing it, shortly before reaching the sand, when my line of sight reached beyond the hill in front of me, the lighthouse, about three-quarter miles down the coast. A new wave of enthusiasm rushed over me!

We stepped off the road, stretching another 400 feet or so before terminating at an old wooden cabin along the western edges of Fourmile Creek, the same creek seen earlier from the top of the hill. Walking alongside the property, marked only by a wooden fence, barely removed from the sand and heaps of tide-gifted driftwood, we approached the curious building: four corners, grayish wooden facades, and a roof with 2 slightly angled sides, with a chimney pipe, and at least a half-dozen windows, with its backend facing the ocean; and a second similar-looking cabin beyond it, not 50 yards away, larger, with a one-sided sloped roof and an added deck with wooden railing, resting gently against the nearby hill.

This time, I hardly noticed the crunch beneath my feet, taking my first steps onto the beach, my boots submerging slightly beneath the grit of shifting sands. The creek poured down from the canyon’s open mouth onto the beach, with scarcely a bank to regulate its flow, meeting the familiar coastal waters, coalescing in a brackish pool. The shoreline coarsened with the rising tide as we hiked along the estuary, and through the creek. The trail lifted slightly, barely ascending the tideline, then narrowed back onto the turf, as it serpentined along the coast. With a widening stride, we approached the lighthouse.

The lighthouse stood proudly atop a small terrace overlooking the beach, its eastern wall nearly flush with the quickly rising hill behind it, minus a few feet. Its base was a small white rectangular concrete structure with one door along its southern wall, and 5 large vertical windows; 2 in the back, 2 in the front facing the ocean, and one on its northern end. From its center arose the lighthouse gallery, a small metal octagonal platform guarded by rusty railing, and encompassing the lantern room, which was itself supported by X-shaped lattices, under a domed cupola, rising to a height of 27 feet.

The interior consisted of two small, vanilla-clad rooms, marred in graffiti, and peeling paint, each with two closets, on either side of a central stairwell, interrupted by a large metal column, leading to the gallery. I sucked in my gut and ascended the spiral staircase up into the gallery, then into the “darkened” lantern room, its light having been removed long before our arrival.

I spent a moment there in quiet observation, as I took in the surrounding area. Roughly 100 feet to the north stands the oil house; its oil tanks still present, now empty and rusted over. Such a container burst open in the early morning hours of January 22, 1923, spilling about thirty gallons, as this quiet beach community felt the tremors of a 7.2-magnitude earthquake, recorded off Cape Mendocino, further up the coast.

Turning west, dozens of blackened boulders, each of a different form, lie sprinkled unevenly along the water’s edge; and beyond them, a featureless horizon, obscured by the still-present sea fog; and to the south, a rusty boiler, from one of the area’s many famed shipwrecks, partially submerged beneath the surf; a strange comfort for a pod of mammoth-sized elephant seals, encircling the rusty scrap.

It was here, along the bench overlooking the ocean, where a home once stood, followed by a second, and a third, with a barn further still. Unfortunately, I’m about 50 years too late to see them. Maintaining such a remote lighthouse was a costly and complicated endeavor, so when there was no more need for a manned lighthouse, the Coast Guard opted for a lateral marker, somewhere offshore. Subsequently, maintenance fell under the responsibility of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Squatters occupied the abandoned structures, and after a number of failed evictions, BLM decided to burn every wooden structure to the ground, in 1970. The nearest town to Punta Gorda was, and still is, Petrolia; an eleven-mile journey, weather and tide-permitting. Remote as it is, and with its neighboring structures long gone, it truly is the loneliest lighthouse I have seen.

With our time at Punta Gorda coming to an end, we began the hike back to the car. Retracing our steps, we found our way back to the road that had previously delivered us to the beach. So began the 1.5 mile hike up a grueling 1,000 foot ascent. I remember seeing the car in the distance as we approached. A feeling of relief swept over me. This adventure was coming to a close, but the next adventure lay ahead of us, further up the California coast!

In 2022, both remaining structures were rehabilitated. Cracked walls were fixed and repainted, and a new spiral staircase was installed.

The lighthouse, and its companion, the oil house, were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Sources

lighthousefriends.com, “Punta Gorda Lighthouse”.

United States Coast Guard, “Punta Gorda Lighthouse”.