Roughly centered 30 miles down the I-40 between Flagstaff and Winslow, taking a dedicated exit marked “Two Guns,” will take you to a forgotten place, the likes of which modern civilization had only begun to tame as the grip of the Wild West began to loosen. This place, once a bustling must-stop off the Mother Road, Route 66, is today, reduced to little more than a collection of rock walls and graffiti. Despite decades of neglect and vandalism, however, these walls still have a story to tell; a story to which, even the ground on which they stand, gives utterance.

Before Two Guns and possibly the arrival of Athabascan tribes, Apache and Navajo; this land was host to Native American activity, according to artifactual evidence found in the area, potentially reaching back a millennium. With the arrival of the Old World, white settlers began to arrive in the form of traders and frontiersmen.

Athabascan culture had already, prior to their arrival, been firmly cemented in the area, for what could have been centuries. Despite their cultural differences, the Navajos and settlers maintained peaceful relations. That was, they did, until the hand of the U.S. government, in the form of the Calvary, disturbed the peace. In 1864, with the U.S. having acquired the Arizona territory only the year before, and with the “Indian Wars” still underway, members of the Navajo tribe were being rounded up and sent to the reservation at Fort Sumner, New Mexico. Many of these same Navajo, after being released 4 years later, would return to the area. It was around this time that the legendary outlaw, Billy The Kid, and his gang of criminals, was rumored to hideout in the area. This is easily disproved, however, as official documentation puts him in New Mexico at the time.

If you wanted to claim the next decade of activity as the true origins of Two Guns, you wouldn’t hear an argument from me. For it was in 1878, after a longstanding conflict between the Navajos and Apaches, when their violence came to a head.

The Apaches, according to this story, had raided an encampment of Navajo, looting the area, and killing everyone they found, with the exception of 3 young girls, whom they killed elsewhere. Only to once again, shortly later, extinguish another Navajo encampment; this time, killing everyone.

For a short time they, the Apaches, had eluded the fury of the Navajos; as they bunkered down in a hidden cave, with their horses and valuables, near a bend in Canyon Diablo. The truth of how they were discovered has conflicting stories, but the most likely indication was rising heat coming up from the ground. Gathering sagebrush and other flammable materials, Navajo warriors set fire to the only exit from the cave, and killed anyone trying to flee.

In a panic, with no other perceivable options, they slit the throats of all their horses, stacking the bodies near the entrance. This proved futile, however, and it wouldn’t be long until the cries of death gave way to silence. When the smoke finally cleared, with their vengeance complete, they entered the cave, retrieving their stolen goods, and plundering what was left. The suffocated, lifeless bodies of 42 Apaches were all that remained. This would later become infamously known as Apache Death Cave. It’s important when covering these events not to be too dogmatic, as we have no way of knowing how much of the story is indulged, or even if It’s true. More on that later.

The slaughter between tribes was not enough to sway the burgeoning of white settlers. Their westward economic expansion was delayed, nonetheless, with the imposing gorge that was Canyon Diablo, a 250-foot drop into the Earth.

Lieutenant Amiel Whipple, one of the first to survey the canyon, wrote: “we were all surprised to find at our feet, in magnesian limestone, a chasm probably one hundred feet in depth, the sides precipitous, and about three hundred feet across at top. A thread-like rill of water could be seen below, but descent was impossible. There was not the slightest indication of a stream till we stood upon the brink and looked down into the canyon…”

For this reason, Canyon Diablo, the town, was born; established just east of its namesake, and roughly 3.5 miles north of the cave. Diablo was never intended to be more than transient. Its existence would not live to rival the town of Two Guns, which at this point was still decades off. There are many stories surrounding Diablo, but in order to add perspective, we should first cover Two Guns.

Homesteading became popular in the area over the coming years. With the establishment of the National Old Trails Road, a 3,096 mile-long, coast-to-coast highway, in 1912; and later a bridge over the canyon; traffic was sure to follow.

The town that would later become Two Guns first began as a modest Trading Post, named Canyon Lodge. There were two homesteading families in those early years, both credited with its creation in different literature. It’s unclear to whom goes the credit, but the earliest of the two were the Oldfields, who settled in 1914. The Cundiffs, Earl and Louise, would follow shortly later, in 1920.

Whomever built Lodge, it seems it was owned and operated by the Cundiffs, after their purchase of 320 acres of land, on either side of Canyon Diablo. Lodge would soon grow into a gas station and restaurant, serving natives, travelers, and cowboys, alike. Later, with the completion of Route 66, this same building would become a Texaco Service Station, and the local post office. The fuel island, on which the pumps once stood, is still visible today.

There was a certain man living in the area at this time. This man, Harry “Two Guns” Miller, an eccentric, known to be of a violent and unstable persuasion, would be the primary catalyst for the creation of Two Guns. He claimed full-blooded Apache heritage, even dubbing himself, “Chief Crazy Thunder,” and wore long braided hair, to sell the image.

In 1925, Miller leased some land from the Cundiffs. With the assistance of local Hopi men, he transformed the simple trading post into a full-fledged tourist attraction; the crown jewel of which became a roadside zoo, replete with mountain lions, gila monsters, and other desert creatures. A shop, living quarters, and other accommodations were also constructed. He called his creation, Fort Two Guns.

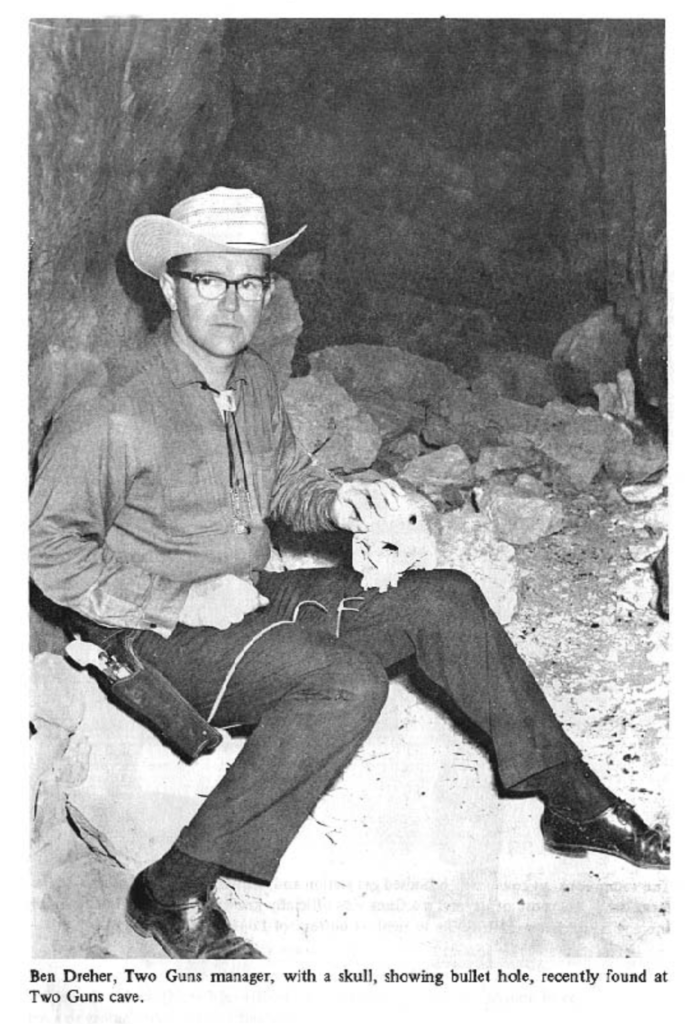

Miller held no qualms about exploiting or embellishing the area’s dark history. For that matter, he took no issue with outright deception, either. Structures were erected inside and outside the cave, deliberately crafted to resemble dilapidated ruins. He branded the underground cavity, “Mystery Cave,” and sold entry permits from the ticket office overlooking its entrance, which still stands today. Never wasting the chance to make a buck, he installed vending machines in the nearby “ruins,” and allegedly sold the skeletal remains found within the cave to interested tourists.

Disputes erupted between Miller and Cundiff; and on March 3rd, 1926, during a heated argument over the terms of his lease, Miller shot and killed an unarmed, Earle Cundiff. Some sources allege this happened in the streets, others say it happened in the room directly to the right of the zoo’s entryway, and still others say, it was Miller’s home. Despite his crime, Miller was acquitted for “self-defense.” Miller would leave the area for a short time, but not before taking, in no small amount, articles of silver, turquoise, and other valuables.

When he did return, as if to add insult to injury, he tried to acquire the land for himself, claiming ownership with the courts. The bereaved widow, Louise Cundiff, would spend $15,000 in the ensuing court battles before her title was cleared.

Two Guns endured for some time along Route 66 until the completion of Interstate 40. Unlike route 66, which passed directly through the center of town, the newly-minted highway would bypass it altogether. This was the beginning of the end.

In an attempt to regain lost tourism, Louise and her new husband built a second Texaco Service Station, and another zoo on the north side of the canyon, in-view of passing motorists. This is why if you visit today, you’ll see evidence of the zoo on both sides. In spite of their efforts, it was doomed for failure. They sold Two Guns in the 1950s.

The land would change hands multiple times over the next decade until it was purchased by Ben Dreher, who went to great lengths revitalizing the area. It seemed, at last, the town had a new lease on life.

It wasn’t meant to be, however. In 1971, the gas station blew sky high, taking the entire town with it in an incredible inferno, the smoke from which could be seen all the way from Holbrook. The town was never rebuilt. Due to the many misfortunes of the area, many consider Two Guns to be cursed.

A rumor has circulated the internet in recent years that Two Guns was purchased by actor Russell Crowe, in 2011, for a West World remake. This is false. As far as I can tell from my research, Historic Two-Guns Properties LLC, in Flagstaff, is the legitimate owner.

Although the ghost towns of Canyon Diablo and Two Guns are separated by decades, and their creation and destruction came about for different reasons, they share a geographical connection along the same canyon, separated only by a few miles, and as we’ll see, much of what we “know” about Diablo, came from Guns.

If you’ve heard anything about Canyon Diablo, the town, not the chasm; you’d know it to have been the deadliest town in the Arizona territory. Tales of greed and bloodshed permeate almost every legend that persists to this day.

As mentioned previously, Diablo was not made to last. Its entire existence came about for the construction of the railroad bridge over the chasm. So when finished, so, too, was the town. It is said, however, when the bridge was nearing completion, that it fell short of the necessary length by several feet. This, combined with financial difficulty, caused the construction to linger until 1890 — a full decade.

These were the final days of the Wild West. Law would come soon, but not soon enough. According to legend, the town’s first lawman, after having assumed the badge, was killed 5 hours later. So rampant was violence and murder, that men were buried where they were slain, as the cemetery had overflowed.

There was no “Main Street,” in Diablo — the main drag was known only as Hell Street. Populating the road, and the different corners of town were 4 brothels, a couple dance halls, over a dozen saloons, and almost as many gambling houses; to the benefit of 2,000 townsfolk.

The most interesting thing about these grandiose stories, as far as we can tell, is they’re all fake; the work of Gladwell Richardson, a novelist; whose interest in Diablo probably came from proximity, as he worked in the Two Guns trading post. Anything you hear of Diablo should be taken with a pinch of salt. Returning to my earlier comment about the history of the Apache Death Cave, this may have been another fabrication or exaggeration by Richardson.

There seems to be no trace of this overpopulated cemetery mentioned in his stories, and there are only a few graves to be found in the area; like that of Herman Wolf, who ran another trading post until his death.

There are still standing walls visible today, one of which reaches at least 15 feet tall (not that I measured). Near to this, you’ll find a large subterranean cistern, covered by an arched roof. It’s likely, however, these postdate the town of legend, though pegging down a date would be difficult. The fact is, the temporary nature of Diablo suggests less-than-permanent accommodations. Something resembling a camp with basic wooden facades is probably more accurate. It’s also possible, though I can’t find any records, that this may have been Canyon Diablo Station, which, by the way, was the scene of a train robbery in March of 1889, as documented in the Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner, a Prescott newspaper.

The town undoubtedly had its vices: alcohol, gambling, prostitution, etc. If there was a need, someone was willing to meet that need. Most often this came in the form of, “Camp Followers”, According to an archivist of the Arizona State Railroad Museum, this was big business. As railroad companies provided basic necessities, the followers provided everything else.

While the town surely did not resemble the stuff of legend, we can assume it to have been a rowdy place. Many of the men who worked here were single, or away from home for long stretches of time; and as a consequence of its temporary nature, it lacked basic law enforcement.

When the work was finally brought to completion, the town was disbanded, as the workers continued westward. Although the bridge was later replaced, the foundation pillars are still visible today. If you look hard enough, you might also find artifacts, such as railroad spikes, or bolts. No written records were ever kept, and subsequently, as that generation slowly passed away, so, too, did the memories of everyday life in Diablo.

Sources

Legends of America. Two Guns, Arizona – “Death By Highway.”

Legends of America. “Canyon Diablo – Meaner Than Tombstone.”

Bob Baker. “Canyon Diablo Train Robbery.”